This is a segment from the Forward Guidance newsletter. To read full editions, subscribe.

I’m old enough to remember when, just a few months ago, the Trump administration talked about cutting deficits to 3% of GDP.

Ever since the Liberation Day pivot, however, the Trump administration has 180’d on its goals and is now pushing a new way to manage the US debt situation: Run it hot.

Oftentimes, the zeitgeist of a moment can easily be encapsulated by a meme:

Last week, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent hinted at this pivot in a CNN interview:

“There is the potential growth of the debt, but what’s more important is we grow the economy faster. I inherited a 6.7% deficit as a percentage of GDP, and we’re trying to bring that down by decreasing spending, increasing revenue and [growing] the GDP faster than the debt.”

Read between the lines of Bessent’s quote and you realize the implications for owners of US Treasurys.

Luke Gromen said it best:

This is financial repression in action: Grow the way out of an elevated debt/GDP ratio by making bonds yield less than the growth rate of the economy.

For example, if bond yields remain fixed at 4% but the economy grows at 6% nominally, you can outgrow the debt since the yield is fixed and will become less of a burden over time as higher revenues make it less burdensome.

I’m sympathetic to the idea Bessent articulated during the interview: The White House wants to cut spending and increase revenues. However, squaring that idea with the House tax and spending bill, just passed overnight — it doesn’t quite pass the sniff test.

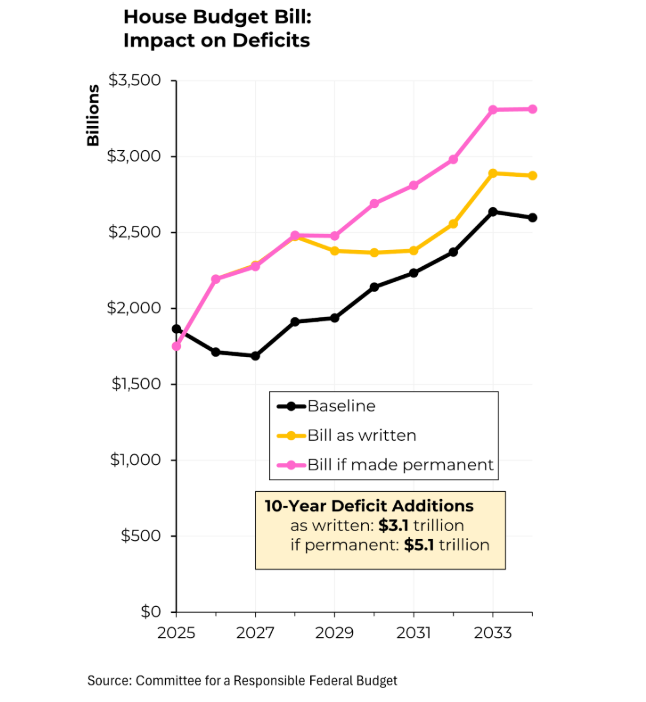

The new bill would increase deficits by nearly $3 trillion over the next 10 years:

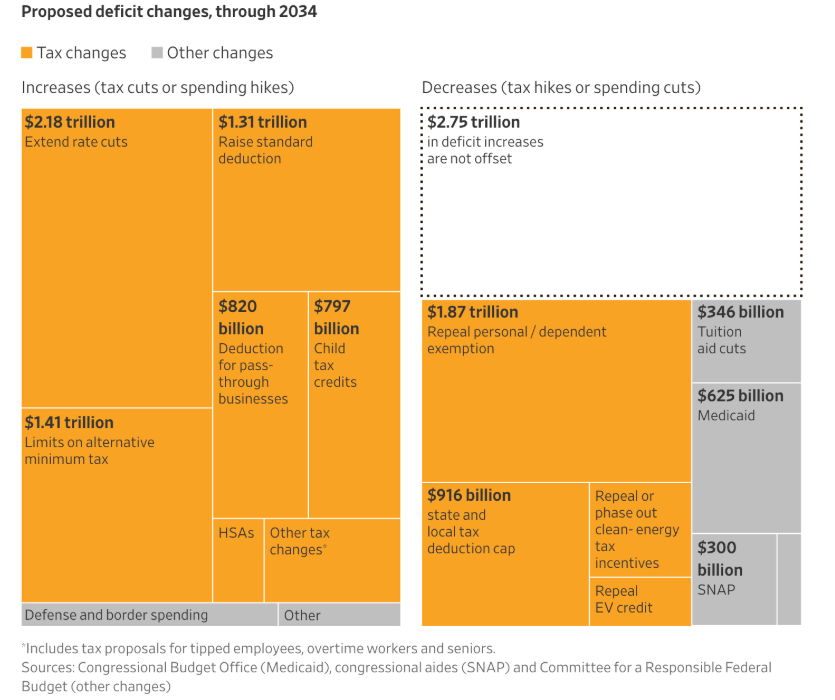

Breaking down the calculus, a significant amount of the bill’s spending will need to be funded by higher debt issuance:

Source: Wall Street Journal

To play devil’s advocate, the scoring and measurement of this bill is fraught with inconsistencies that should be acknowledged:

- It doesn’t account for increasing tariff revenues to partially offset this bill. An effective tariff rate of 15%, which is roughly where things stand today, would bring in $300-$400 billion a year. This would help partially offset the widening deficit, but not entirely, and this revenue certainly wouldn’t be the golden goose that the Trump administration hoped it would be so as to narrow the deficit to pre-Biden levels.

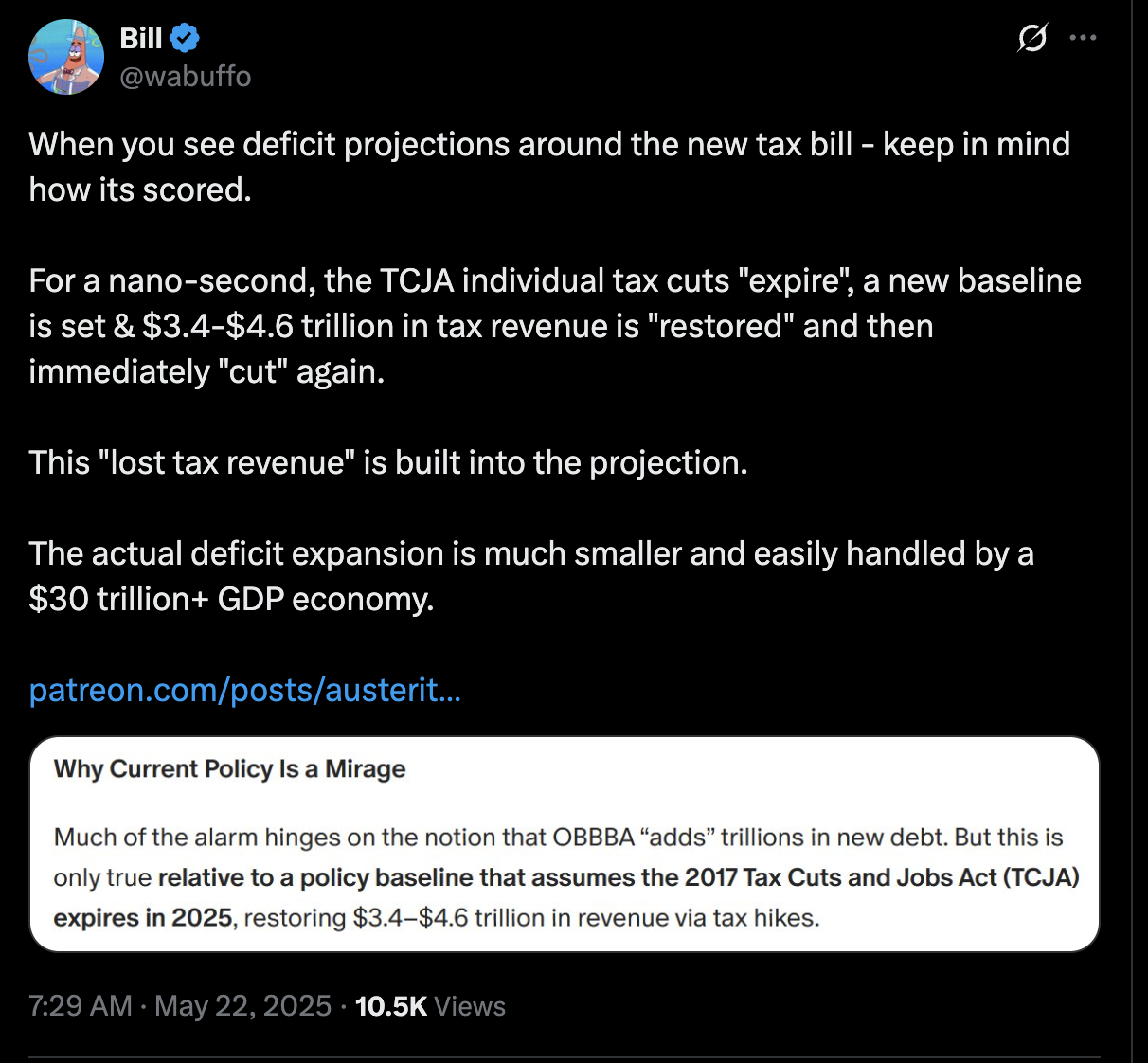

- The scoring in the bill assumes a quick expiration of Trump’s first-term tax cuts that then get reinstated afterward, leading to a superficial surge in tax cuts despite them being net-neutral.

Source: @wabuffo on X

Leave a Reply