This is a segment from The Breakdown newsletter. To read full editions, subscribe.

“Macroeconomics in this original sense has succeeded: Its central problem of depression prevention has been solved.”

— Robert Lucas, 2003

I’m old enough to remember when people thought recessions might not be a thing anymore.

By the early 2000s, economists like Robert Lucas and Alan Greenspan argued that traditional recessions, in which a cyclical decline in demand led to a shrinking economy, were becoming an endangered species: less frequently seen and less dangerous when they were.

This was known as “The Great Moderation,” but just as the idea was catching on, it was seemingly discredited by the “Great Recession.”

There was nothing moderate about the 2008 recession: Peak to trough, US GDP fell 4.3%, the largest decline since World War II.

That should not have discredited the moderation thesis, however, because the Great Recession is more accurately known as the Great Financial Crisis — a financial own-goal that had little to do with macroeconomics.

Nearly two decades later, the US still hasn’t experienced a recession in “the original sense.”

The last traditional, business-cycle recession was way back in 1991, when Fed Chair Greenspan raised interest rates to 10.5% and unemployment rose to 7.8% — and even that was considered a mild downturn by the standards of the time.

In the 34 years since, we’ve only had three recessions and they were all triggered by non-cyclical shocks: the dotcom bust and 9/11 in 2001, the financial crisis in 2008, and the Covid pandemic in 2020.

As recently as last week it seemed like we were inevitably headed for a fourth.

But this week, markets rallied on a rising consensus that we’d avoid it yet again.

Which makes me wonder: If a sudden trade war can’t tip an aging expansion into recession, what can?

Is it only pandemics and banking accidents that cause recessions now?

Probably not.

But equally, Greenspan was probably right that the recessions we do have will be less frequent and less severe.

His hypothesis was based primarily on a belief in “better monetary policy,” and that seems to have been borne out: If Fed Chair Powell guides the US to a soft landing despite pandemic-induced inflation and tariff-induced uncertainty, I expect he’ll go down in history as the second greatest central banker of all time (behind only the patron saint of inflation fighting, Paul Volcker).

Another reason Greenspan cited for optimism was the ongoing “shift away from manufacturing toward services,” and that, too, might now be vindicated: This week’s market action seems to suggest that even a 10x increase in tariff rates won’t derail the US economy.

“The more flexible an economy,” Greenspan concluded, “the greater its ability to self-correct in response to inevitable, often unanticipated, disturbances and thus to contain the size and consequences of cyclical imbalances.”

The US economy, he explained, was getting more flexible thanks to automatic stabilizers, just-in-time logistics, deregulation and the “increased depth and sophistication of financial markets.”

More sophisticated markets give policymakers better information to work with — and the best information, of course, comes in the form of charts.

So let’s see what they’re saying.

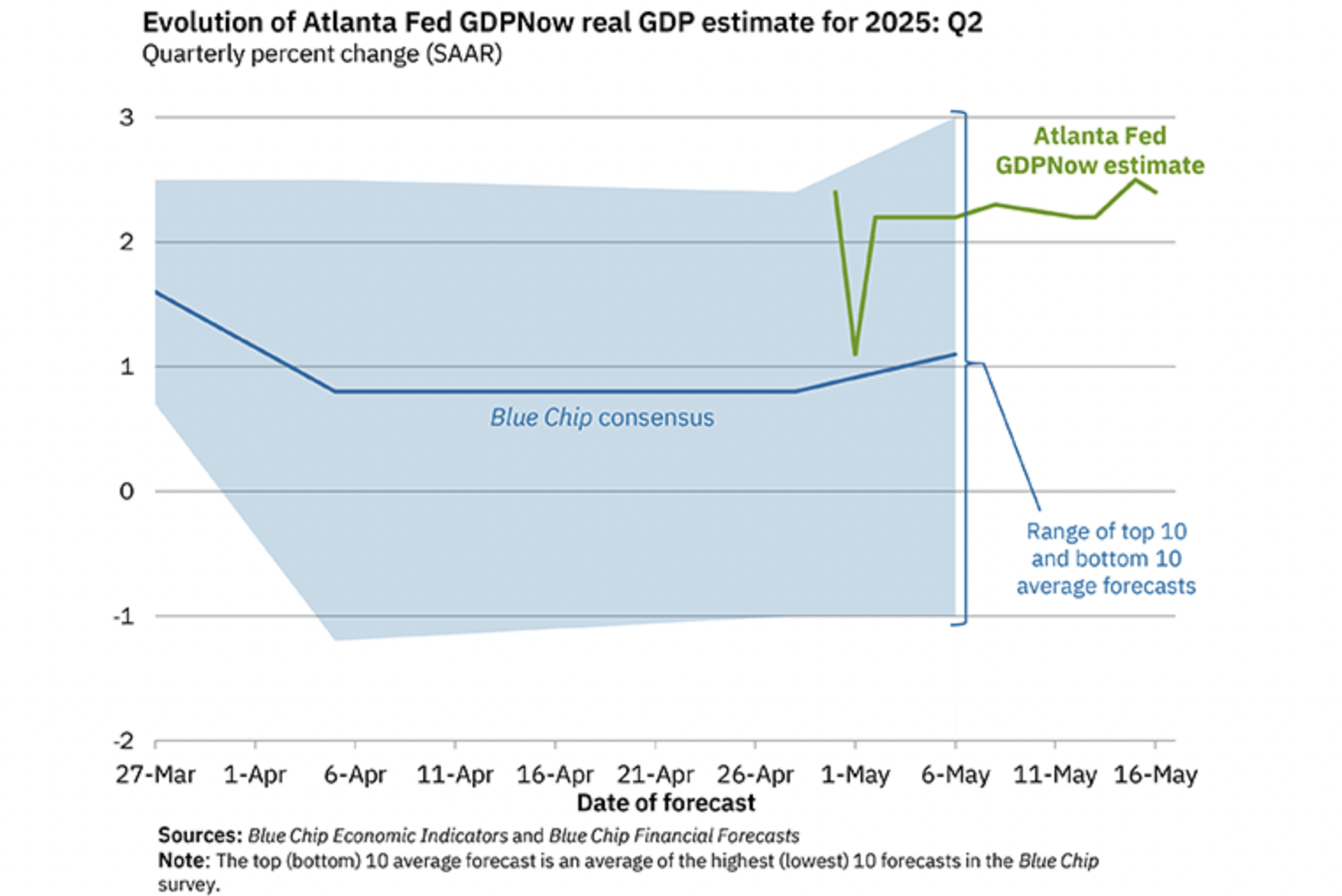

It won’t be this quarter:

Suddenly, the next recession seems as far off as ever: The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model sees the US economy growing 2.4% in the current quarter.

It’s unlikely in Q3 or Q4, too:

Polymarket odds of a US recession in 2025 are down to 36%.

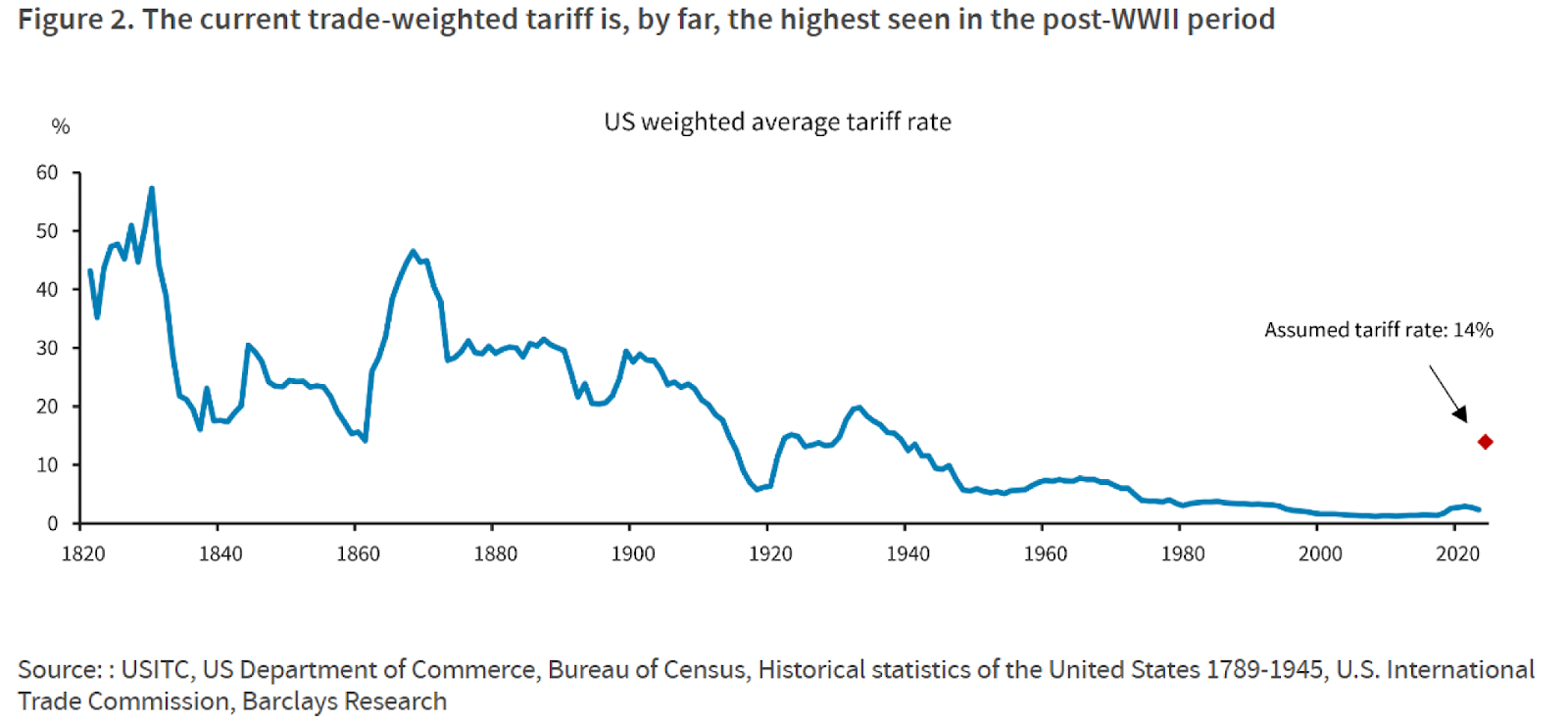

Are tariffs priced in now?

Barclays Research (via the Odd Lots newsletter), estimates that the current trade-weighted US tariff rate is now around 14% and analysts at Goldman Sachs said it “would probably remain elevated for the foreseeable future.” That’s lower than expected just a couple of weeks ago, but we may not be out of the woods yet. President Trump said today that, because there are too many countries to negotiate with, he will unilaterally decide tariff rates sometime in the next two or three weeks.

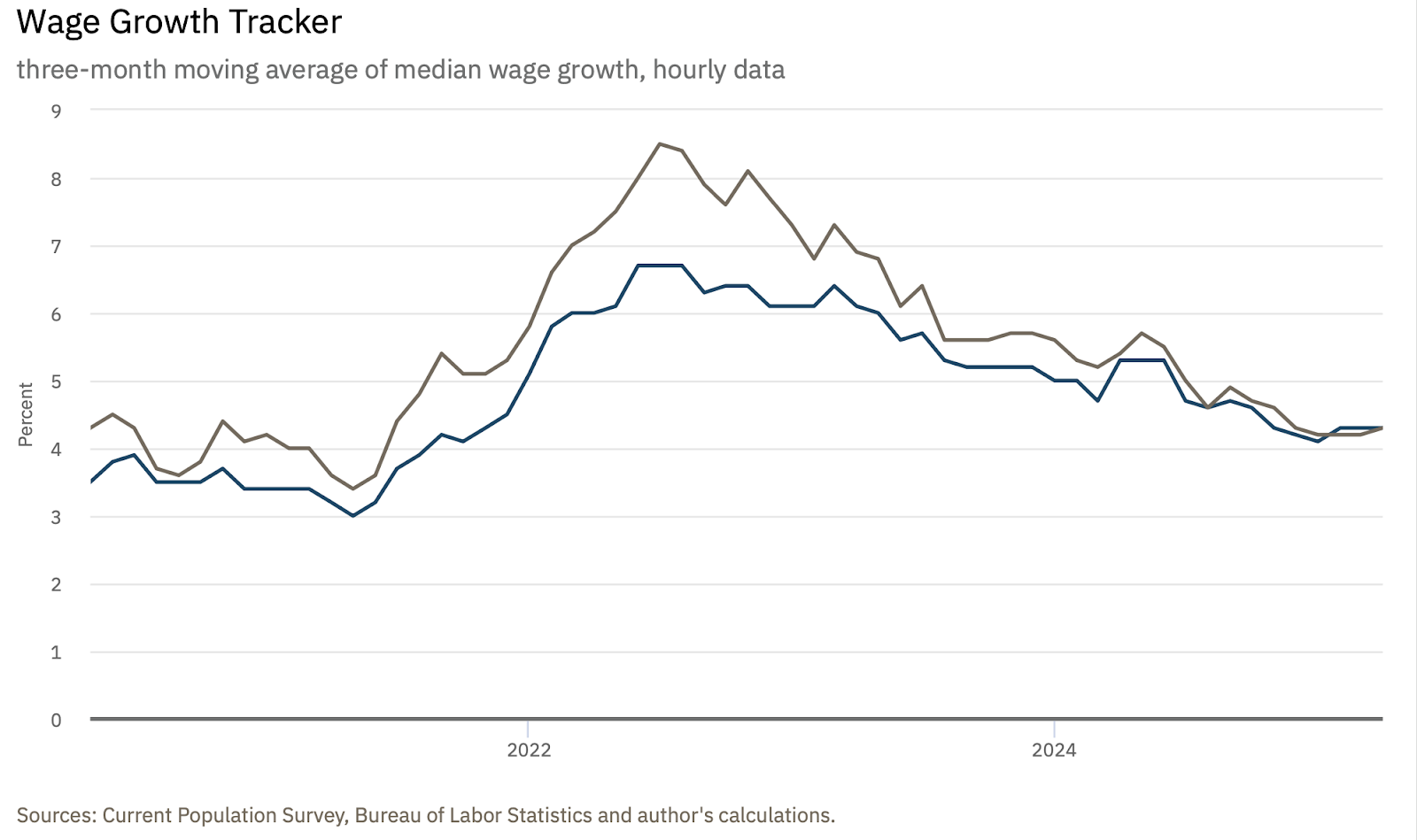

Wages > inflation, still:

US wages are still growing at 4.3%, according to the Atlanta Fed — well in excess of CPI, which ticked down to just 2.3% in April. The top line above is wage growth for job switchers, which may have further to fall: The Wall Street Journal noted this week that two-thirds of US workers believe they are overpaid.

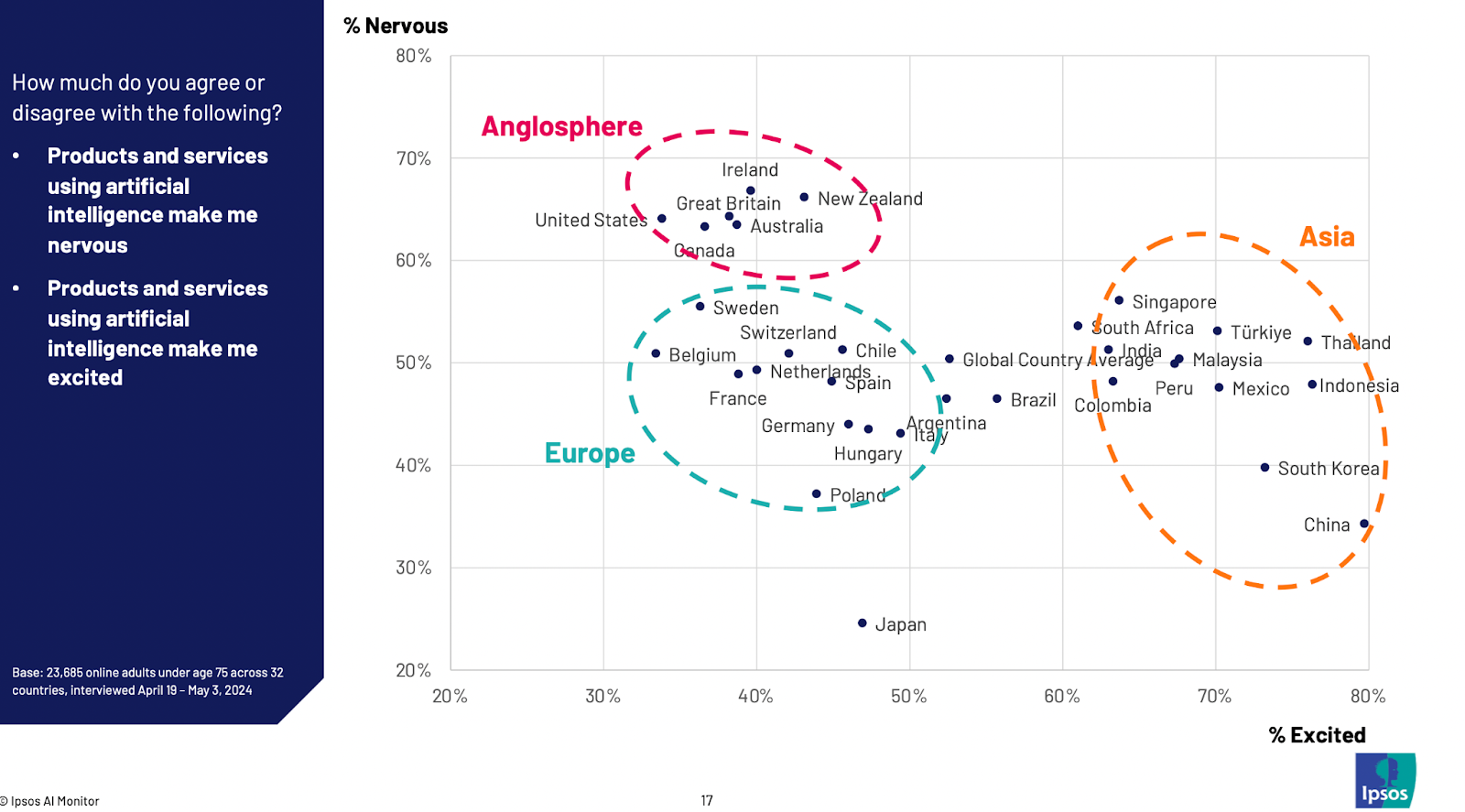

Apropos of nothing:

This is from 2024, but I only found it this week: An Ipsos survey found that Asian (and some Latin American) countries are “excited” about AI while Europe and the Anglosphere are “nervous.” Let’s check back in a decade or two and see if that’s correlated to growth rates. (I suspect it will be.)

Why Joe Rogan should be for free trade:

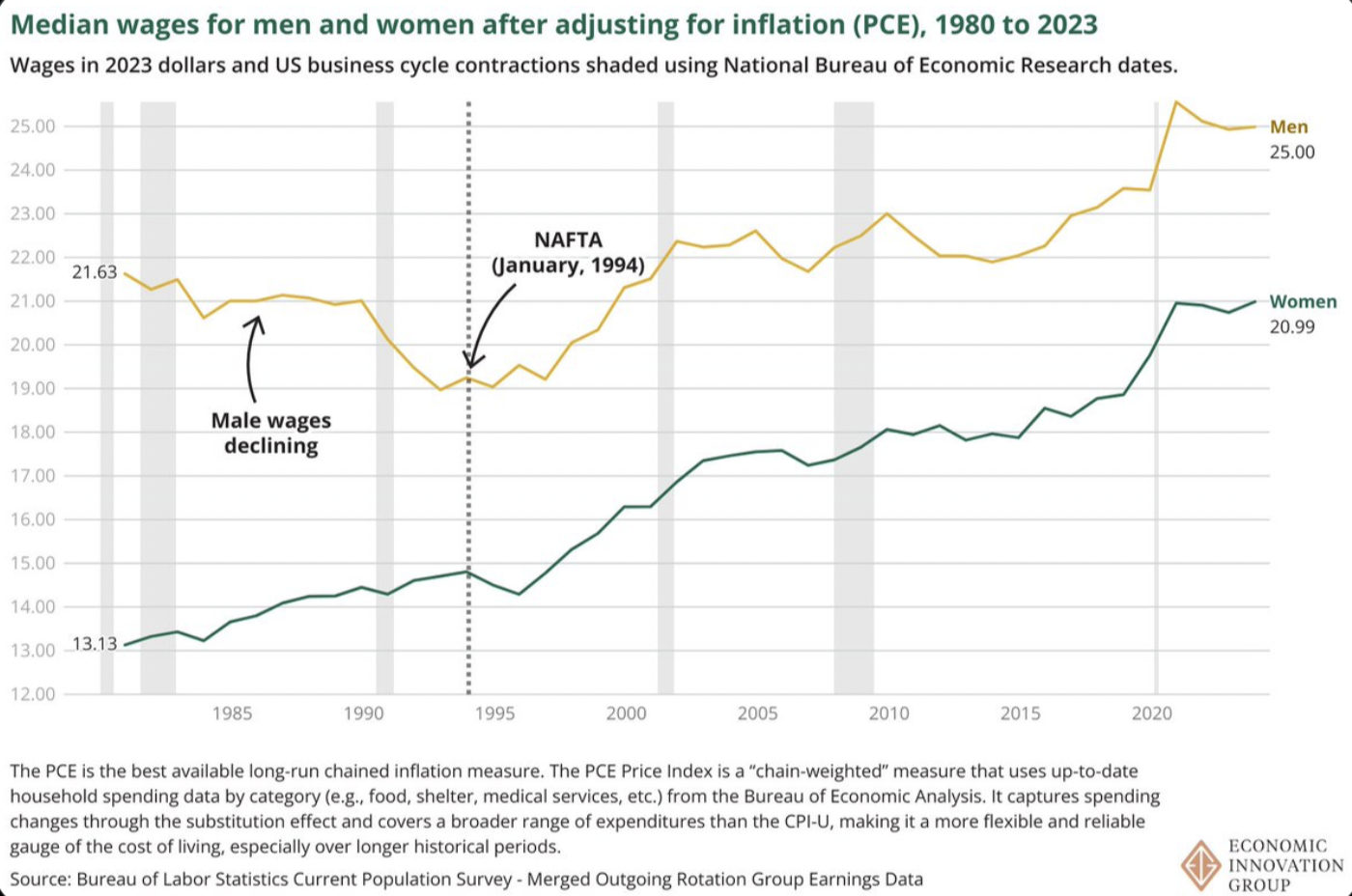

John Lettieri notes that the beginning of globalization (marked by NAFTA in 1994) was coincident with a trend change in male earnings: After two decades of decline, male wages began rising again.

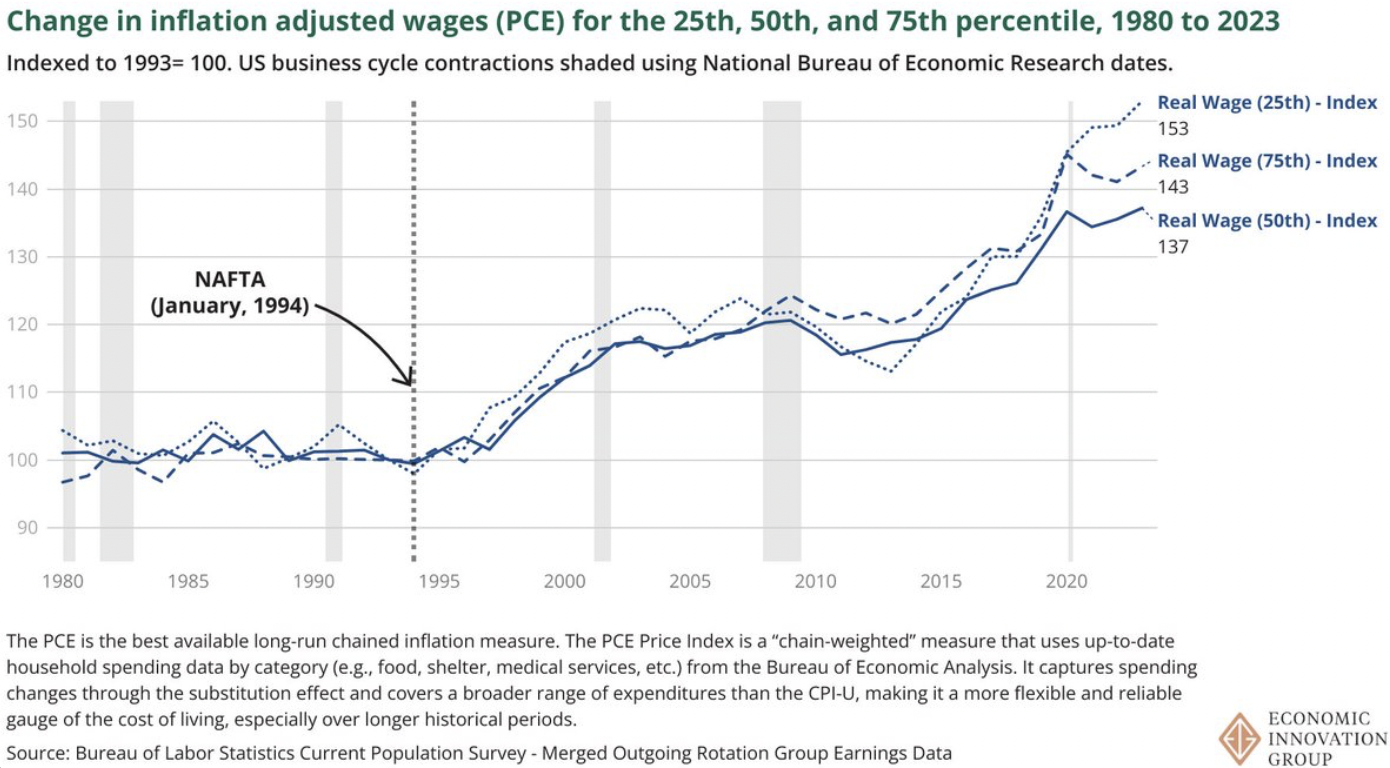

Why everyone should be for free trade?

Lettieri also finds that, starting with NAFTA, wages for the lowest quartile of earners rose faster than wages for the top quartile. If, like me, you enjoy these kinds of narrative violations, his full thread on trade is a must-read.

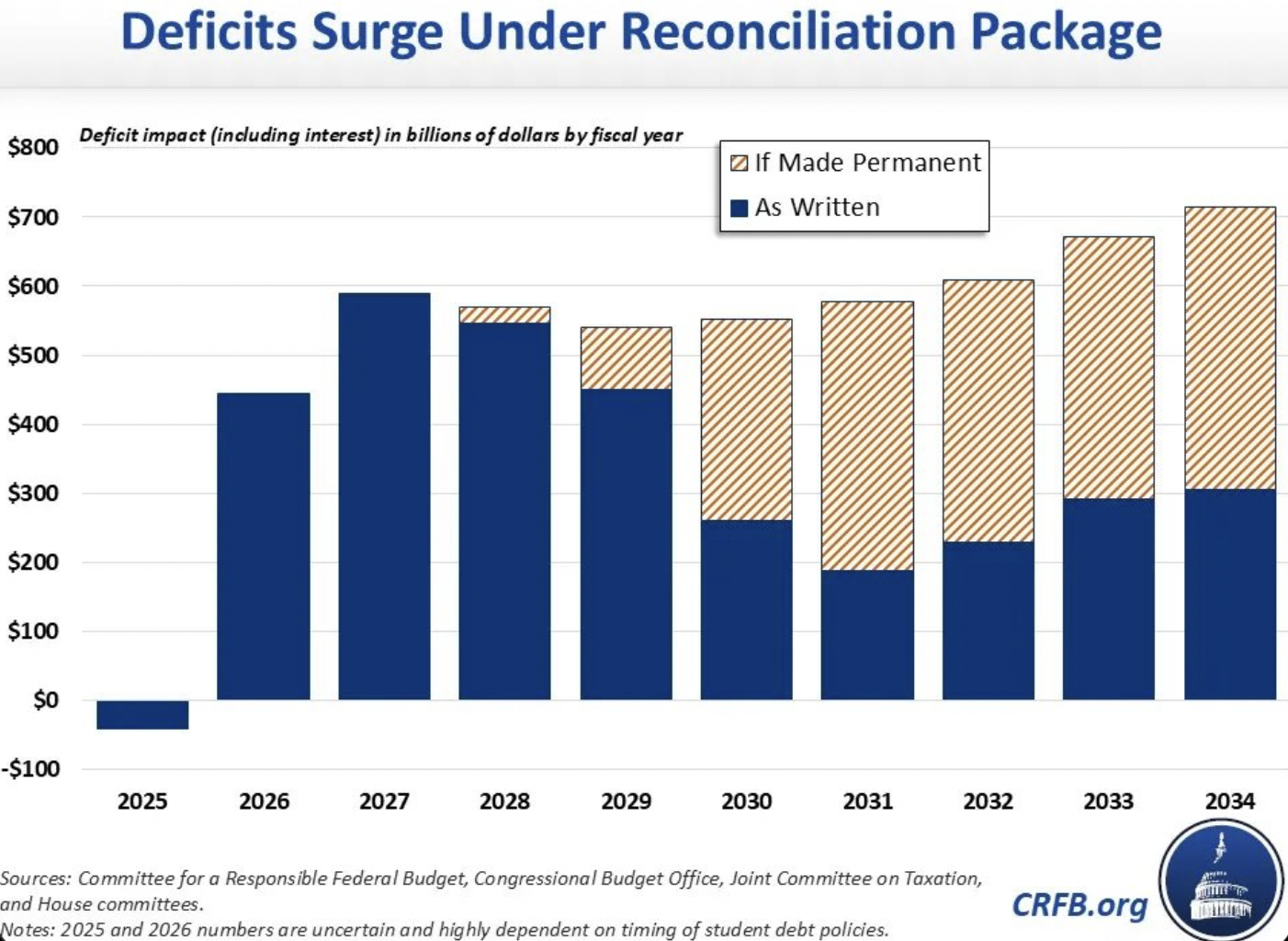

The other deficit problem:

The current House budget proposal would add $3.3 trillion to federal debt through 2034. It probably wouldn’t pass the Senate, but it seems a safe bet that whatever eventually does will be only marginally more responsible.

In good times and bad:

The really bad news about the US budget is not that it’s running a big deficit — it’s that it’s running a big deficit while the economy is booming. What’s this chart going to look like in the next recession? (If there ever is one.) Also, if your goal is to reduce the trade deficit, running a trillion dollar budget deficit year after year is, uh, not the way to do it.

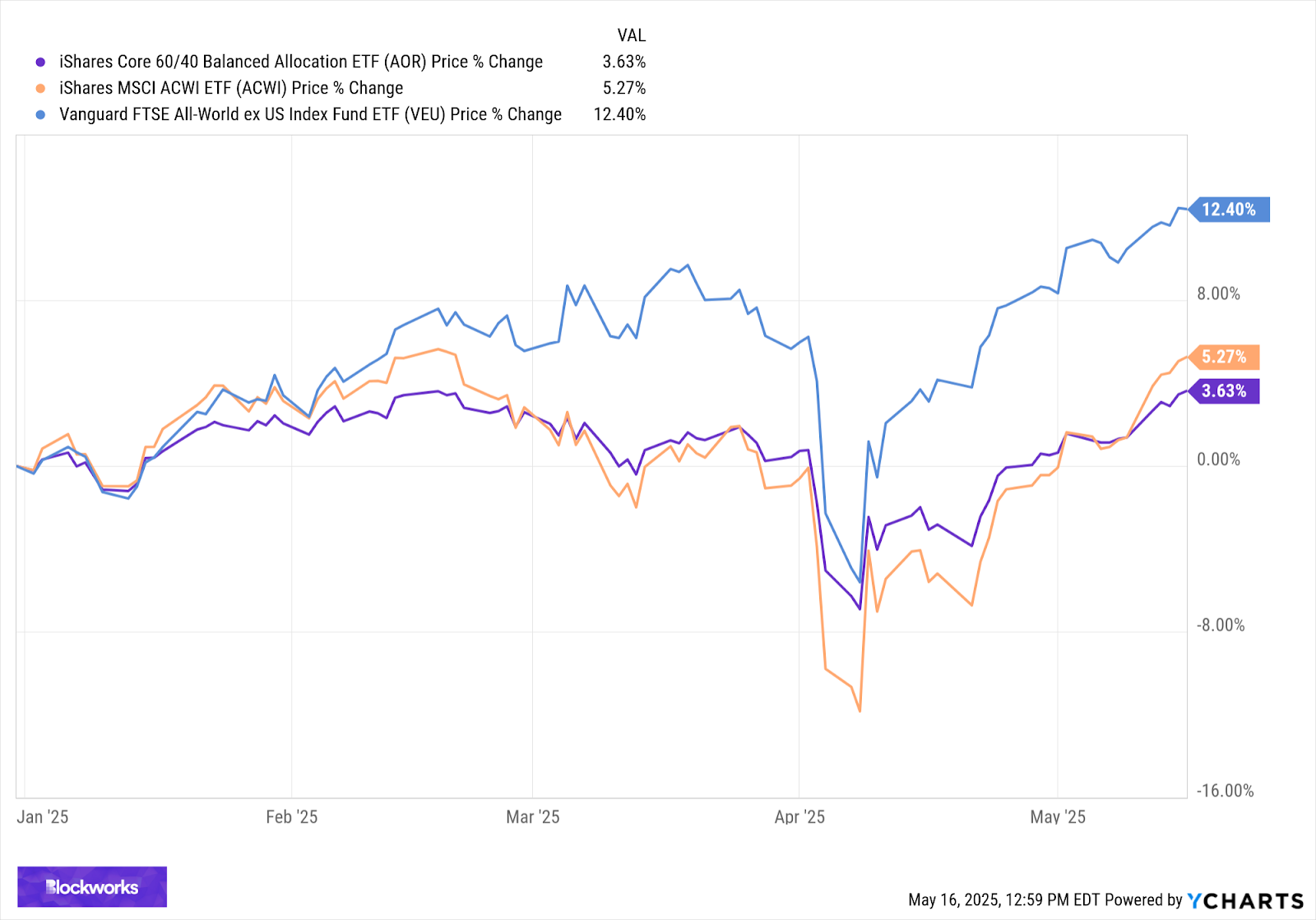

Deficits are good for business, though:

Global equities (orange) and a 60/40 portfolio of global stocks and bonds (purple) both made all-time highs today. Global equities ex-US (blue) made the highest highs.

Leave a Reply